on

Public Buses Travel in Many Directions, but Not That One

The most pivotal component in any delivery network is the regional distribution centre, where a high volume of units are collated, catalogued and consigned for dispatch. In the business of transporting marginalised people between marginalised places, the units processed seem to have certain ideas and a certain agency of their own, and so, for the sake of distinction, a more specialised term is used: bus station.

For technocrats with an appetite for efficient infrastructure, there are two ideal models of bus station available á la carte: the correspondence model; and the frequency model.(1)

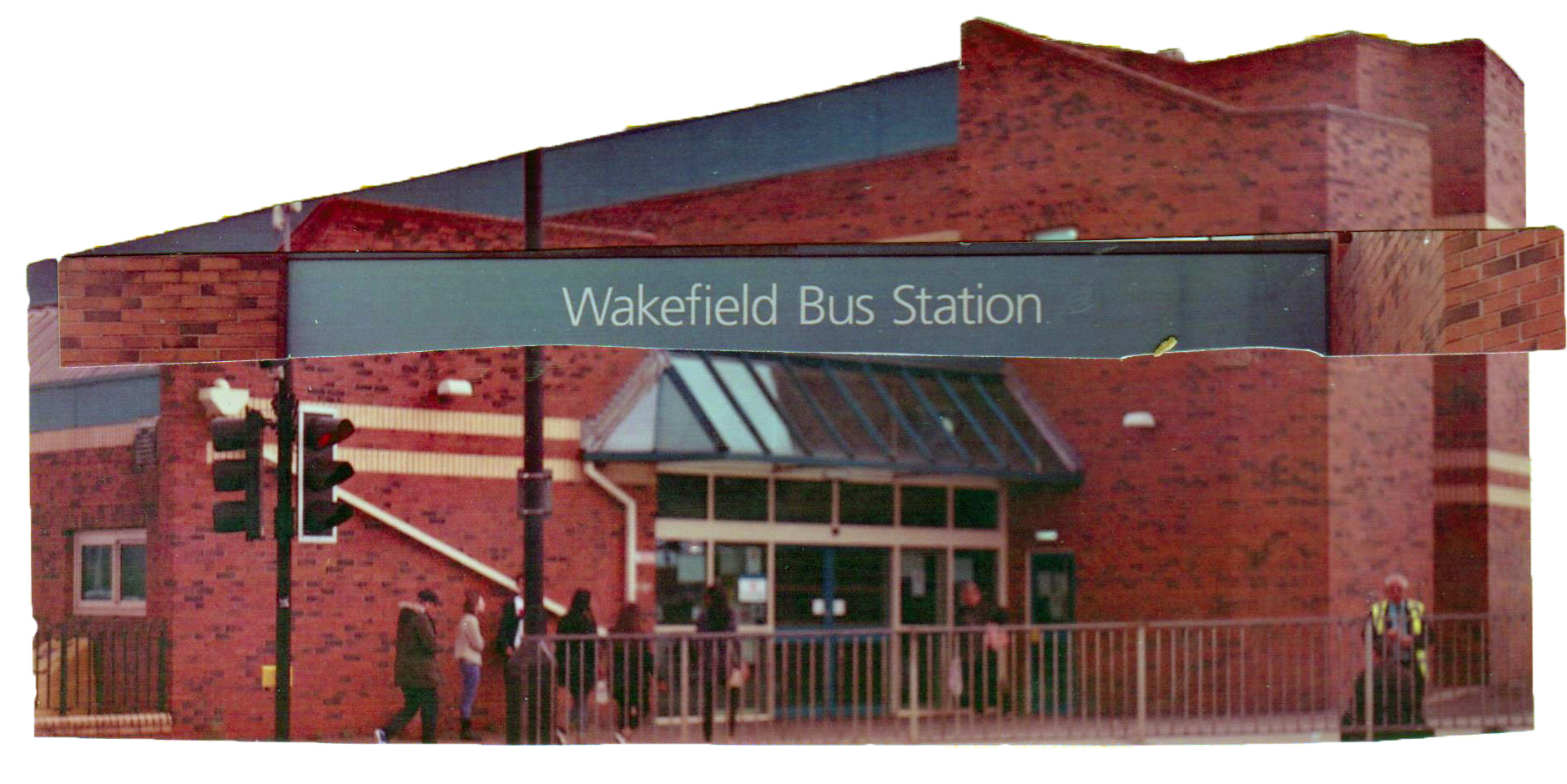

Wakefield bus station, however, is marked by logistical laxity and so the dish served is inevitably not as advertised. The station’s large geographical footprint suggests it was built to the correspondence model but the buses do not correspond, and neither are they frequent. There again, designs, models and concepts never do quite pan out as conceived in the planning office or the architect’s studio – not if anyone living is involved.

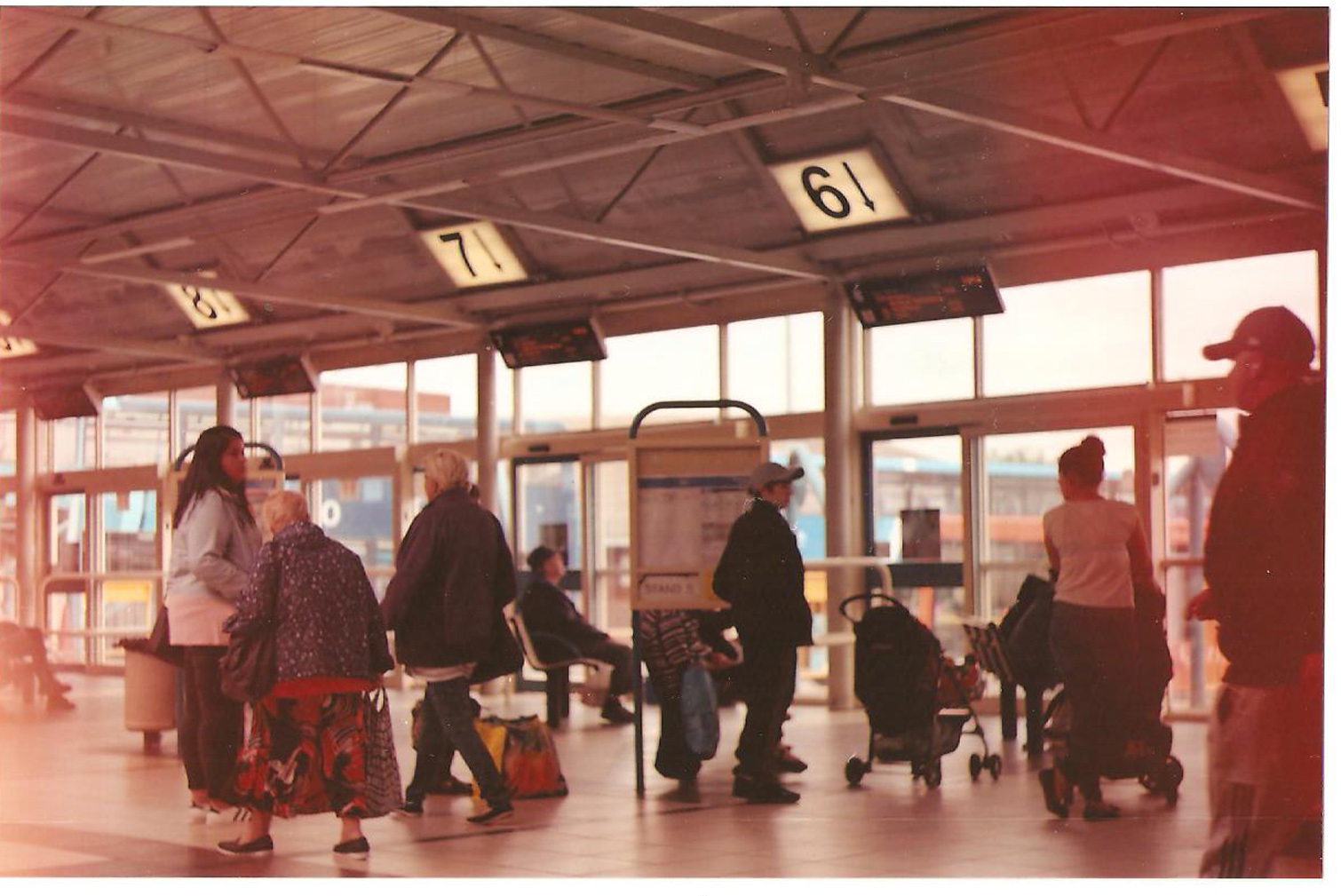

Arrivals do not correspond, then, and departures are sufficiently frequent only for any given passenger to miss any given bus while sufficiently infrequent such that the passenger must wait a lifetime for the next one. What results is a delicious, if unintended, fruit. Wakefield bus station becomes a de facto repository of brilliant mystique; there occurs an alluring accumulation of sublime everyday characters.

The very mobile men and women have four wheels, one underneath each corner of their car, allowing them to circumvent the bus station, which is just as well because motorists are by far the demographic with the most colossal concentration of thoroughly dull individuals. To be sure, bus stations are reserved for only the most beautiful and exquisite blokes and blokesses. These people are those who lack the economic means to drive, or else are inhibited by age or disability.

This section of society reliant on public transport are stiff but not static, all thanks to the embittered breed behind the wheel. Bus drivers are critical to the whole operation. To ensure these vital workers are of the correct calibre, and to guarantee poor customer service, candidates for the role must be cynical at interview and provide references attesting to acrimony. All bus drivers are issued with uniform, keys and a standard e-cigarette which many choose to upgrade at their own expense. Vaping is bus company policy because, enshrouded in a flavoured mist, a driver’s sense of time becomes distorted and this inconvenience can then be passed on to paying passengers.

For this reason, the 104 is late to depart. As they wait, Jean Bowers and Gwen Pickering discuss minor home improvements and, beginning with the most recently installed fireplace, mention in reverse chronological order family members who have had work done. The more the bus is delayed, the more the two ladies become increasingly peckish. But Jean Bowers is a woman of mettle and resolve. The Wagon Wheels inside her shopping bag are to last all week and so remain untouched for the time being. The bus is by now very late but the women do not mind because senior citizens receive a free bus pass, and free vinegar is sweeter than honey.

In a direct display of disrespect to the ham and cheese sandwich in her handbag, a Level 1 Hair and Beauty student is less austere and buys a pasty from Greggs. Upon leaving the popular bakery chain, however, she regrets an error in her calculations. Actual queuing time far exceeded predicted queuing time, and the 189 through Castleford is en route without her, leaving the tight-trousered sixteen-year-old to learn independently the underpinning principles of shampooing and conditioning. Others in education, meanwhile, forego their buses deliberately. They find their particular institution alienating, or it is Thursday and undressing for PE is an immediate prospect inducing anxiety.

Against the back wall by the disabled toilet, a placid staffie sulks in solidarity with her sullen owner, who bears an unsaid grief. The stocky dog is unsure what begrudges the man but bows her head anyway and frowns out of loyalty. Anyone seeking to intervene, asking the owner, ‘what’s up with you?’ on behalf of the dog, will be promptly told to piss off.

If the dog owner’s knickers are in a twist, he is at least in a building where a more comfortable pair can be purchased. Knicker Man (Richard) displays his stock of intimate womenswear from a likewise intimate market stall in the southern end of the bus station, having sought refuge there when the council capitulated and agreed to sell the city’s market hall to the developers that besieged it (2). The stall serves an older clientele who wish to comprehensively cover their bits. The underwear for sale is, therefore, at the more conservative end of the spectrum, which reflects quite acutely the sole trader’s modest lifestyle. Knicker Man is an honest man and a humble man. He has been content for over thirty years to pay the mortgage, feed the family and partake in the pub quiz on Wednesday nights; never pretending, nor intending, anything more.

Knicker Man finds pleasure in his work - it is hard not to when a workplace offers such outstanding vistas. He sees: tracksuits and greasy hair; supermarket uniforms; single mothers; Fultons Foods shopping bags; rigger boots; kids with scooters and whole packets of custard creams; old men with flat caps; old women with flat shoes; schoolgirls on the defensive; schoolgirls on the offensive; chaperoned folk with learning difficulties; rugby league shirts from many seasons ago; temporary warehouse workers; poor immigrants; and refugees.

Knicker Man may not travel by bus but he spends the majority of his time in Wakefield bus station. In the first instance, Knicker Man is a person of Wakefield bus station; he is just as ordinary, just as powerless, just as brilliant, and just as beautiful.

…

Passengers-to-be typically stand or sit as they wait to embark their bus, but Knicker Man has come to know through astute observation that perching brings benefits of both. With the vantage of standing and the comfort of sitting, he thumbs through the local newspaper as he rests lightly on the front corner of his stall. He permits himself to read a pair of short articles because there are no interested customers currently browsing bras.

As part of a council press release on the inside page, the word ‘development’ is conspicuously preceded by two intangible adjectives: ‘creative’ and ‘cutting-edge’. It proclaims a multi-million pound vision of urban and economic regeneration through cultural institutions, creative industries and artistic installations. Wakefield, it is promised, will be transformed into ‘the creative heart of the North’, and it all smacks of a quite ideal spectacle.

Knicker Man’s lower back communicates via a different medium that the benefits of perching are only temporary. Fifty-nine years earlier, Jane Jacobs(3) wrote that “government administration officials … do not invent planning theories nor, surprisingly, even economic doctrine about cities. They are enlightened, and they pick up their ideas from idealists, about a generation late.” In an act of twisted homage to the urban studies luminary, or else out of ignorance, planners and politicians of Wakefield have taken Jacobs’s sharp indictment as an instruction.

The idea of the ‘creative city’ has been socially divisive and economically disappointing for almost twenty years, and ‘culture-led’ regeneration is a horse flogged worldwide before now. Reproducing a well-worn concept is fine where it works, only the initiatives in question have had miniscule, if any, success elsewhere(4). But marginal towns and cities in decline must at least try, and if it was not one of these formulas, it would be another from the same shelf – maybe the ‘high-tech’ or the ‘green’ city.

If Knicker Man is not au fait with urbanism fads of the last two decades, it is because he has had more immediate concerns, such as a life to live. If he is unacquainted with certain ideological spaces that exist only intellectually, it is because his life has been more concretely emplaced. This notwithstanding, the news of redevelopment strikes him as ominous for reasons of his own. Experience, after all, has furnished him with the understanding that current users of a site must first be cleared before any new development can be constructed; and current users do not have much leverage in the matter if they are of an undervalued class, have minimal economic clout and travel by bus.

…

In search of substance, and sweeping aside abstract vocabulary designed to dazzle, Knicker Man reads further. The yield of useful information is relatively low because at this stage the plans are simply an expensive vision, and, in any case, it is standard practice to spout guff in the marketing of redevelopment and regeneration projects. Nevertheless, the details extracted are these:

The proposed plan consists of two ‘hubs’ in the city centre. Hubba hubba. There will be a creative business hub that will house and link cultural organisations, businesses, entrepreneurs, artists and influencers, and there will be a cultural hub with events and exhibitions of culture and art. There will be installations and signposting around the city to complement and link these hubs. Existing ‘assets’ - the theatre, studios, galleries etc. - will be enhanced also.

Knicker Man feels estranged and thoroughly uninspired. The regeneration plans miss a mark which he struggles to call by name. The sanctuary of the bus station is to be preserved, but only by chance, only because it has been overlooked, just as the people thereof have been overlooked on almost all previous occasions. There is nothing positively for Knicker Man or his class of bus station people. If his ruminations are of sufficient duration, he may conclude that cities and in vogue regeneration concepts are not designed for his class of people because his class of people do not design cities or in vogue regeneration concepts.

Knicker Man has been to three art museums in fifty-six years. On each occasion, he nipped around the whole place in less than ten minutes. If all art institutions of credential take it as their task to stir feeling and inspire profound questions, the feeling evoked in Knicker Man was a sense of absurdity and the series of questions were, ‘Why must I pay £8.00 to park the van?’, ‘Why must the objects on display be so incomprehensible?’, ‘Why must the room be so big when it contains so little?’, and, above all, ‘why do people come here?’

Amongst those in the bus station, only a handful have been to a gallery or museum more times than Knicker Man, and none of them have the skills, taste or social contacts to work in the industry. From Wakefield bus station, therefore, people travel in all directions, but only very rarely in the direction of creative industries and institutions of Culture.

For all the talk of culture, it is not the culture of Knicker Man or anyone else in the bus station. It is a higher culture. A refined culture. Culture with a capital C. It is the performing arts. It is fine art. It is literature. It is poetry. It is fashion. It is a closed section of society open to all. All those with privilege, that is. All those who have cultivated a taste. All those who have studied. All those who have grown up in a house with books. All those whose family, friends and teachers discussed with them these products of prestige. All those who had been taken frequently to visit these institutions.

There is an unmistakable senselessness to the regeneration plans; a conspicuous discrepancy between their pretension and reality. The city council is to make an inaccessible provision for the people it serves. This senselessness depletes Knicker Man from the inside, affecting within him an untenable and disorientating vacuum. When people find themselves in an absurd or untenable situation, they can attempt to change it or they can remove themselves from it entirely. Opting for the latter, Knicker Man discards the newspaper and heads for a general chinwag with Sandra, the woman who sells birthday cards from the adjacent stall. Together they sip tea from a flask and chew over moral conundrums – ‘should I feed the cat that comes into my garden?’ etc.

…

Lovely Man, a regular bus station user and top bloke with a tremendous fleece, takes it upon himself to write a letter to the city planning officials after attending a public consultation. Although planning consultations are generally more a device to manufacture consent and thereby legitimise and validate decisions already made, Lovely Man responds politely and in good faith:

Dear Mr XXXXXX XXXXXXXX,

I was pleased to meet you at the public consultation (30/01/2020) regarding development proposals for Wakefield city centre. Following the consultation, I write to detail some reflections and judgements.

Let me first state my position clearly: I do not oppose per se the council’s plans to reinvigorate the city centre, I write only to warn against expecting any positive change resulting from them.

The intentions of the plans are good, and aiming to re-centre the city after many years of de-centring is long needed. As far as the proposed developments will inject new activity on sites where there is currently none, the plans are necessary, however, as I will outline, not sufficient, and not without shortcomings to be addressed.

The idea of the ‘creative city’, in various forms, is not a new one, neither is the initiative to make ‘Culture’ a central tenet of an urban vision. The evidence, as far as I can find any, on creative and culture-led regeneration is either inconclusive or, in fact, shows it to have had no significant impact(5).

To cite examples: the Middlesbrough Museum of Modern Art, in the centre of Middlesbrough; our own Hepworth Gallery; the Sage and the Baltic galleries in Gateshead; and even the O2 Arena in London. The surrounding areas of these places display very little, if anything, in the way of increased activity or improved economic performance.

The reasons for the underwhelming impact of such projects are manifold, but essentially amount to a case of the cart coming before the horse. What makes for a prosperous and active city is places of work - particularly highly skilled work. It is skills, business, infrastructure etc. that determine a cities fortunes. Paul Swinney(6) writes,

“The fundamental challenge that struggling places face is to attract more business investment in high-skilled activities, which in turn will create more and better-paid jobs. One of the principal reasons they find this difficult to do is because they haven’t got the skilled workers that high-skilled businesses are looking for. The opening of a cultural institution doesn’t change this, as it doesn’t improve the skills of existing residents. It is also unlikely to attract-in skilled workers from elsewhere either, who will look for the availability of a job first, then weigh up the cultural offer of a place after.”

Culture-led regeneration schemes, therefore, often do not tackle the more fundamental causes of decline. The new proposals for Wakefield city centre have the same problem.

Furthermore, such schemes fail when they are envisaged in isolation, and they are preoccupied with simplistic visions which misconceive real life in the city. As such, they implement one-dimensional concepts and utter simple statements in response to complex problems. They neglect the basic fact that what constitutes a city is a multitude of diverse people and activities which are, moreover, overlapping and interrelated.

Consider this thought experiment: would Wakefield have avoided altogether the decline of its city centre if, all else being equal, it had had in the precinct performance and gallery space?

The answer to my mind is no. Only a small proportion of people organise their spatial activity in terms of attractions of higher Culture and facilities of professional creativity. The decline of the city centre has been multi-causal, and so the response must be multi-faceted.

A healthy, busy and sustainable city centre is fundamentally of mixed-use and mixed-users, because this ensures the area is populated and active at all times, making for better security and a positive sense of place. Whereas the proposals for Wakefield city centre are dominated by a single type of use – or very similar uses - of space by a single type of person (more on the homogeneity of users below).

For a city centre to thrive, it has to be of everyday use value to a variety of individuals and communities. There must be homes and workplaces; leisure centres and clinics; markets; free and open public spaces etc. These fundamentals ensure daily, ongoing activity in a space, and only on such solid foundations can it be enhanced by novel, in vogue projects.

The plans proposed at the public consultation do not sincerely meet these conditions of diversity and everyday mixed-use, owing to the general and absorbing application of a singular, abstract, trendy theme (Culture and Creativity) and a narrow offering in terms of concrete developments and activity thereof. As such, the plan is condemned from the beginning.

What is more, the ‘cultural sector’ is a relatively closed segment of society. Its institutions favour those of a certain class, who already possess the correct cultural capital, as defined according to the dominant hegemony of a higher Culture, to access and appreciate the value of their offering. Many in the sector, and city planners of a similar background, do not fully understand how unlikely it is for working-class people to visit their attractions. Events can be made free of charge but if they are not appropriate to the needs and socio-cultural dispositions of Wakefield residents they remain exclusionary, only more subtly.

The data shows cultural engagement in England to be low(7). I suspect in the case of Wakefield this will be more acute, and a majority of Wakefield residents will be indifferent to, even alienated by, the cultural offer of the plans.

As such, the plans fall short on the creation of a participatory space, where people feel they ‘fit in’, and can develop an affective sense of place.

The proposed developments could be framed as essential workplaces, boosting jobs in the city centre; the problem is that employment in the cultural and creative sector is marked by significant exclusions of those from working class social origins(8). Occupations in these industries are not accessible to all and, considering the demographic of Wakefield, not accessible to most people living in the city.

In one sense, a barrier to entry is removed by bringing the industry to Wakefield, as high costs of living - such as they are in London where most of the industry is concentrated - are reduced. Nevertheless, significant exclusionary barriers to employment will persist. These include: a geographical skills gap; the prevalence of unpaid labour (internships being the common route of entry) and unfairly paid work (through freelance work, temporary contracts, traineeships, or project-based work); knowing other creatives is essential for finding work; and cultural tastes play an important role in getting into upper-middle class occupations. Hiring can be a form of ‘cultural matching’, excluding those who do not have the shared values, attitudes and tastes of specific social groups. This is especially true in cultural and creative occupations.

Hence, the proposed cultural developments will appeal overwhelmingly to a certain liberal section of the middle-class with the cultural capital to access the new spaces, and any new jobs will be to the benefit of those with certain privileges.

I suspect, moreover, that visitor numbers will increase only on weekends and during certain one-off events. Both the type of activity and the people partaking are thus restricted and, in turn, not conducive to a revival of the city centre which depends on mixed-use by diverse groups at all times.

There is a further, more philosophical, reason the plans will not enliven the city centre: ‘Culture’ and ‘Creativity’ suggest life and activity, but there is a disparity between the pretension and the reality of these themes in urban development.

Conceived spaces of culture and artefacts of creativity are typically managed for presentation during short visits. Here, ‘culture’ is prescribed and on offer only during visiting hours. Creativity and culture are necessarily packaged and presented for easy and quick consumption, and, in turn, reduced and reified to still objects. The mode of interaction is confined largely to looking and listening – making for a passive and one-directional relationship between space and user; users of space become spectators. This does not apply to those working creatively – artists, video game producers etc. – but, as I have outlined, those in this group are a skilled and privileged few.

On such an account, it seems that diverse, always unfolding inter-activity is foregone. Instead spatial participation is largely, though not entirely, restricted to the passive reception of ideal, timeless and inert artefacts. If liveliness and variety attract more liveliness whereas deadness and monotony repel life, then a new space of passivity, closed to spontaneity and appropriation, will hardly reinvigorate the city centre.

To conclude, when the evidence on regeneration through cultural and creative industries is inconclusive, even showing it to have failed in places, I find it puzzling that Wakefield council’s strategy is to invest primarily in this narrow sector. It seems particularly inappropriate to Wakefield by virtue of the sectors tendency to exclude the working class. In this light, it does not seem a rational or sensible response to inactivity and disengagement in the city centre, although it may be fashionable and exciting to the disconnected professionals making the plans.

At the consultation, you described to me the creative and culture-led strategy as a risk; it must be said that this risk will not pay dividends unless consolidated with spaces and activity of everyday mixed-use value, and investment in high skilled employment.

Now, I appreciate it is much easier to find fault with urban plans than to provide a positive alternative. I cannot produce an alternative master plan over the weekend following the consultation. Concrete proposals are difficult and constrained by a number of factors – not least conditions placed on funding. For this reason, I sympathise with you, and am inclined not oppose the council’s plans for the city centre, I only advise you that they will have very minimal positive impact.

Yours sincerely,

Lovely Man

(1) On the correspondence model, various buses of various routes park simultaneously, enabling passengers to transfer immediately between lines. This type of bus station is land extensive in order that a number of buses are all able to park.

Bus stations built to the frequency have staggered and, of course, frequent arrival and departure times. The frequency model does not require buses to stop and wait, thus reducing the size of the bus station, if not eliminating the need for it altogether.

(2) The sale was, however, never completed. The market hall remains empty.

(3) Jacobs, J., 2011. ‘The death and life of great American cities’ 50th anniversary ed., New York: Modern Library. (p.16)

(4) What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth., 2016. ‘Evidence Review 3: Sport and Culture’

(5) Ibid.

(6) https://www.centreforcities.org/blog/regeneration-culture-way-forward-left-behind-places/

(7) See Brook, O., O’Brien, D. and Taylor, M., 2018. Panic! Social Class, Taste and Inequalities in the Creative Industries

(8) Ibid.